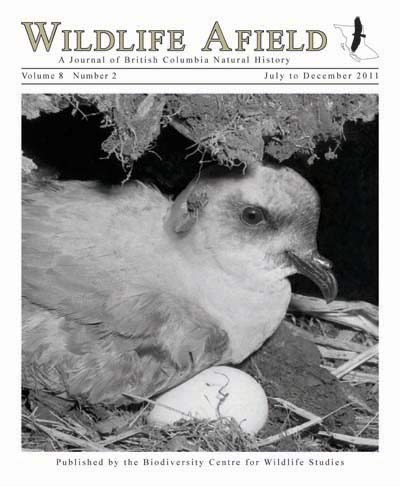

Publication Alert: Wildlife Afield Vol. 8, No. 2

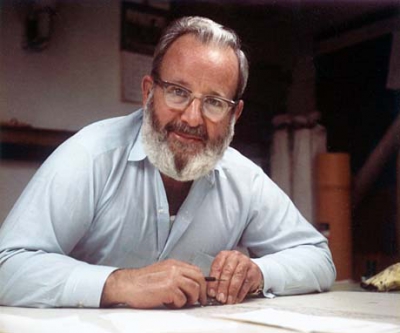

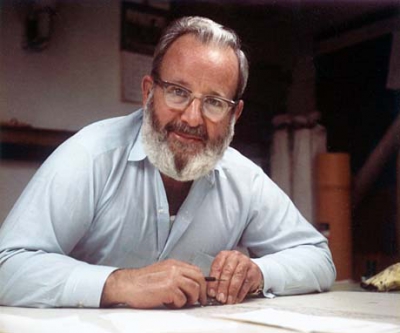

November 14, 2012 – Dr. Ian McTaggart-Cowan book update

The first draft for all chapters in the memorial volume Ian McTaggart-Cowan: The Legacy of a Pioneering Biologist, Educator and Conservationist has now been completed. The authors are presently working on selection of photographs, and other images, for the largest chapter “Memories and Recollections: Students, Colleagues, Associates and Friends.” Once completed, each “memory” will be sent to individual contributors for final approval and then to our peer-reviewers for one last edit. Meanwhile, the images for the chapter are being custom-scanned, ready for publication.

· Ron Jakimchuk, friend of Ian McTaggart-Cowan, with Vivian Banci checking snow characteristics and cover lichen on Caribou winter range northeast of Yellowknife in 2005.

Overview of Dr. Ian McTaggart-Cowan Book. pdf

Back to top

Publication Alert: Wildlife Afield Vol. 8, No. 1

Cover image: Osprey with take out. Flickr c c image. Photo by winnu

Cover image: Osprey with take out. Flickr c c image. Photo by winnu

The 143-page issue includes two “Feature Articles” and six “Natural History Notes” along with regular sections on “Wildlife Data Centre Report”, “British Columbia Round-up”, and “Book Reviews.” A six-page “In Memoriam” for Miles Timothy Myres (1931-2009) written by Martin K. McNicholl is also included.

Most of the publication comprises an article by Gary S. Davidson on the nonpasserine birds of the Nakusp, New Denver, and Burton region of southeastern British Columbia. This major work includes previously unpublished observations and notes from J.E.H. Kelso, a pioneer collector who lived on the west side of Lower Arrow Lake, at Edgewood, from 1913 to 1932.

Natural history notes include a Coyote/Burrowing Owl incident, predation by Northern Shrikes, Long-billed Curlew records for Haida Gwaii, Cooper’s Hawk and Barred Owl encounter, and American Bittern eggs found in American Coot nests.

Back to top

A Forthcoming book

by Ronald D. Jakimchuk, R. Wayne Campbell and Dennis A. Demarchi

Ian McTaggart-Cowan

The Legacy of a Pioneering Biologist, Educator and Conservationalist

The history of zoological discovery in British Columbia, and parts of the Rocky Mountains of western Alberta, is closely linked with Ian McTaggart-Cowan, one of Canada’s foremost and best-known zoologists and conservationists. Dr. Cowan’s life spanned the golden age of biological exploration and linked him with some of the important early collectors and naturalists whose specimens and observations revealed the distribution of birds and mammals in the province during the first half of the 20th century. Ian was a pioneer among pioneers, in a career that began as a summer student on collecting trips in the field and led to an academic career as professor of zoology, department head, and dean of the Faculty of Graduate Studies at the University of British Columbia.

The Legacy of a Pioneering Biologist, Educator and Conservationist is primarily an appreciation of Ian and his many accomplishments. The book is a celebration of a remarkable man’s life and his numerous roles and adventures. It was originally designed to be a comprehensive compilation of his lifetime publications and intended as a surprise 100th birthday gift to be presented to Ian on the occasion of his centennial birthday celebration on June 25, 2010 at Government House in Victoria. However, Ian passed away 61 days before that occasion was to be held.Subsequently, our volume evolved and expanded in scope both as a tribute to Ian, and to preserve his legacy as an educator, researcher, and conservationist. The heart of the tribute consists of over 100 recollections from former students, colleagues, and friends in a section on their memories of association with Ian. These range from the amusing to the poignant, and reveal many facets of his life and personal qualities.

The book is a valuable documentation of the history and evolution of biological discovery and research in British Columbia, and the emergence of a conservation ethic. It is illustrated with hundreds of black-and-white and colour photographs including images of early family life, students and colleagues, and wildlife. This memorial volume is nearing completion. It has been enhanced by the diligent peer-review of Dr. Alton Harestad, Peter Ommundsen, and Dr. Spencer Sealy, all University of British Columbia graduates in zoology. The book has been a voluntary undertaking by the authors and reviewers since its inception in February, 2010 and will be published in association with the Biodiversity Centre for Wildlife Studies, 3825 Cadboro Bay Road, PO Box 55053, Victoria, BC. V8N 6L8. Please see www.wildlifebc.org for updates and availability.

Back to top

2011 British Columbia Nest Record Scheme

57th Annual Report

The Annual Nest Record Scheme Report should now be in the hands

of our loyal participants. A big thanks to all who contributed

breeding records for 2011.

Available for download here

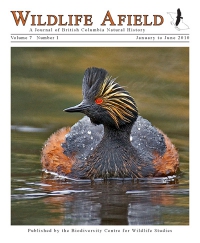

NEW EDITOR FOR WILDLIFE AFIELD

Dr. Spencer G. Sealy

It has been a challenge over the past few months to find a new editor for our bi-annual journal. We preferred someone with a background in natural history, who enjoys and has experience with editing, will encourage professionals and amateurs to publish their natural history observations, and has a history of working with novice authors and eager students. We are delighted to announce that Dr. Spencer G. Sealy has accepted our invitation and will start as editor of Wildlife Afield with Volume 8, Number 1. Wayne Campbell, Pat Huet, and Mark Nyhof will continue in their current roles to complete the editorial team.Spencer retired in September 2011 as professor emeritus of biological sciences at the University of Manitoba. For more than 35 years he supervised about 50 honours and graduate students and was among the founding members of the Pacific Seabird Group and Society of Canadian Ornithologists / Société des Ornithologistes du Canada. He recently completed a five-year term as editor of The Auk, a prestigious ornithological journal published by the American Ornithologists’ Union. He has been recognized many times for his teaching and research activities, including receiving the William Brewster Medal awarded by the AOU for his research on birds.

He is familiar with British Columbia and its wildlife. Although Spencer spent his formative years as a young naturalist and ornithologist in Saskatchewan, he also spent a year as a teenager in Enderby, in the northern Okanagan Valley. Later, after completing his undergraduate degree at the University of Alberta, he attended the University of British Columbia and completed his Master of Science degree on timing of breeding in plankton-feeding auklets on an island in the northern Bering Sea. His passion for marine birds continued into his Ph.D. program while studying the breeding biology of Ancient and Marbled murrelets on Haida Gwaii (formerly Queen Charlotte Islands). Spencer began his academic career at the University of Manitoba in 1972. During sabbatical years, and at many other times, he returned to British Columbia to further his research interests on historical aspects of marine bird documentation and natural history in the province and adjacent regions. He taught seabird courses at the Bamfield Marine Station in the mid-1970s through the early 1980s and supervised field work of three graduate students based at that Station.

While in demand from other academic groups to serve as their editor, Spencer has decided to shift his focus and start his retirement years by catching up on several academic writing projects and also articles focused on natural history that have been on the “back burner.” Fortunately, some of these will be published in Wildlife Afield. Spencer’s first two of many articles on natural history, focused on bats wintering in Saskatchewan and Mallards nesting in trees, were published in Blue Jay, the journal of Nature Saskatchewan (formerly Saskatchewan Natural History Society), in 1960. He submitted his most recent article to Blue Jay less than one month ago. Spencer fondly remembers editors who worked patiently with a beginning naturalist and always encouraged young naturalists to write up their observations. He hopes field biologists and naturalists of all ages will submit articles to Wildlife Afield.

Spencer is well known and respected in the academic community and to have him bring that experience and enduring passion for natural history to British Columbia, and Wildlife Afield, bodes well for fulfilling the mandate of the Biodiversity Centre for Wildlife Studies and what its members support.

Back to top

A Milestone for The British Columbia

Nest Record Scheme

A significant event in the history and growth of the British Columbia Nest Record Scheme happened in 2011. For the past 15 years, a small group of unpaid volunteers have been transferring breeding information from a variety of sources to standard BCNRS nest cards. This year we surpassed our 100,000th historical record and reached a total of 114,249 breeding records.

· Most acceptable breeding records of Great Horned Owl in the British Columbia Nest Record Scheme are of large young visible in the nest or newly fledged young. These youngsters, still incapable of flight, recently ventured from their nest in an old black cottonwood stub in the Creston valley.

The task has been tedious, time-consuming, and at times challenging. In some cases, it took years to obtain specific information for British Columbia especially from oological collections in museums throughout the world and their catalogues that had to be searched for specimens of downy young and altricial nestlings which are preserved in alcohol. Some of the many other sources searched included personal field notes, unpublished reports, technical literature, theses, academic research, incidental observations from hunters and fishermen, correspondence, road-kill databases, wildlife rehabilitation centres, miscellaneous cards from British Columbia in other North American nest record schemes, private egg collections, newspapers, naturalist club newsletters, magazines, photographic files, taxidermy shops, and accessible web pages.

· In the past, egg-collecting was a popular pastime with many amateurs, but today, most oological collections have been deposited in major museums where they can be accessed by interested persons.

The information transferred to nest cards was for confirmed breeding records which included nests with eggs and/or nestlings, newly fledged young being fed, or hatched young incapable of sustained flight. Other observations of birds such as singing on territory, calling from marshes, courtship activities, copulation, adults carrying food or nesting material, adult near nest, juveniles with adults, and agitated adults, are inconclusive as breeding records and are considered behavioural in nature and were added to our occurrence databases. Over the 15-year period we have entered hundreds of thousands of such records, all readily accessible in a unique data field.

· While American Bitterns may be heard calling regularly from marshes and other wetlands throughout the nesting season, their presence does not confirm breeding. Over the past four decades many of these marshes have been thoroughly searched for nesting evidence with very few nests with eggs and/or nestlings or young unable to fly being found. At one small cattail marsh in the central interior of the province, a bittern called for nine consecutive years without nesting.

The routine chore has certainly been meaningful with many new findings. There were new breeding records for the province such as Greater Sage-Grouse. Many were first nesting records for the province including Green Heron, Flammulated Owl, Barred Owl, Purple Martin, Bushtit, and Black-throated Gray Warbler. Thousands of new locations were extracted and many were significant range extensions. Some of these were Pacific Loon in Embryo Lake, Ancient Murrelet at Kelowna, Flammulated Owl and Rose-breasted Grosbeak breeding in the Shuswap Lake region, Double-crested Cormorant in the Creston Valley and Stum Lake, Swamp Sparrow at Dragon Lake south of Quesnel, American Avocet in the Peace River region, Black-necked Stilt, Semipalmated Plover, and Flammulated Owl in the Cariboo region, Eurasian Collared-Dove in the West Kootenay region, Herring Gull at Tunkwa Lake and Scout Island (Williams Lake), Dusky Flycatcher in the Peace River region, Blue-gray Gnatcatcher in BC, Say’s Phoebe in the East Kootenay, Chestnut-sided Warbler at Puntchesakut Lake, Black-throated Blue Warbler in BC, Yellow-breasted Chat at Mission, Lark Sparrow near Hudson’s Hope, Sandhill Crane in the Creston Valley, Lazuli Bunting on Vancouver Island, Painted Bunting at Johnsons Landing, Common Grackle in Fernie. Eight new breeding records for Common Goldeneye on the southwest mainland coast were found as well as unusually early and late breeding dates for at least 28 species of birds. One was a female Canvasback with a brood of eight newly hatched ducklings in the Cariboo on the early date of May 18. A few new hosts for Brown-headed Cowbird were also discovered including two unusual reports of a cowbird egg in a nest of Redhead, Spotted Sandpiper, and Yellow-headed Blackbird!

· The daily field notes of the late J. E. Victor Goodwill, for the 52-year period 1957 through 2009, generates over 110 breeding records a year, mostly from southern Vancouver Island. When the search has been completed for the two filing cabinets of notes, another 5,700+ records will have been added to the British Columbia Nest Record Scheme.

While a good chunk of historical sources has already been gleaned for breeding records, “search and transfer” of pertinent information will continue but at a much reduced rate. In the immediate future, emphasis will be directed toward adding UTM co-ordinates to historical cards, continuing electronic data entry of present nest cards, and updating and organizing species files in the British Columbia Nest Record Scheme so they are more accessible to researchers.

Back to top

WILDLIFE DATABASES - Electronic Data Entry

Four-year Summary - January 2008 through December 2011

Amphibians: 25,834 records.

Reptiles: 19,359 records

Birds: 2,010,136 records

Mammals: 49,027 records

Total Records: 2,104,356

Total Species: 598

Our electronic databases include historic and current information archived in a central repository in Victoria, BC, for all species of amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals that have been recorded within the political boundaries of British Columbia. The province’s location is unique in North America bordering on four United States (Alaska, Washington, Idaho, and Montana) and three Canadian provinces or territories (Yukon Territory, Northwest Territories, and Alberta). Species’ distributions and breeding ranges in British Columbia, therefore, become more important as political boundaries are transcended and political decisions are made regarding a species’ threatened or endangered status.

· When developing electronic wildlife databases, it is critical that information being entered considers the impact of a host of threats that may impact the future existence of a species. With global warming on the minds of many people, BCFWS is making a conscious effort to add historical information on all subalpine and alpine-living species like Hoary Marmot.

The western boundary for the databases extends 160 kilometres (100 miles) offshore and includes details for all living, extinct, extirpated, and introduced species documented in the province.

While most digital wildlife databases include up to seven basic fields such as month, day, year, observer, general location, species, and number of individuals, we are including a minimum of eight additional fields for every record. These include a description of the specific location, National Topographic System (NTS) map grid, Universal Transverse Mercator (UTM) coordinates, sex, age, behaviour, habitat, and elevation. If formation is available, an additional 23 fields could be included making the full complement for a single digital record totaling 38 different fields that can be searched for data. Some of the latter records would include information on source of the record, mortality, recognizable subspecies, evidence of breeding, weather, food or prey, and any other information that enhances the value and interpretation of the record.

· Identifying recognizable subspecies and including details in wildlife databases is value-added information that increases the significance of a data bank. This Northern Flicker, with its gray face, brown crown, and lack of a red crescent on its nape, has been added to our databases as a female “Red-shafted” Flicker.

Although additional time is required to enter a single record, the “value-added” data fields are essential for species’ research, determining long-term trends in populations, interpreting expanding or contracting species’ ranges, establishing sound conservation recommendations, and developing informed management programs in British Columbia. Over time, each record also contributes to a better understanding of the natural history and ecology of a particular animal during its residency in British Columbia. Therefore, recording as much information during the initial observation is time well invested. As Aldo Leopold said, “You can never go back in time for the same information.”

As comprehensive wildlife databases evolve, and grow in size, a much more accurate and complete picture unfolds of how animals in British Columbia lived and depended on the province’s habitats, supplies of food, and shelter for their life requisites. Early publications, fortunately, documented what they knew at the time from information they knew was easily available. While the references were invaluable, no one spent the time necessary to conduct exhaustive searches for additional information recorded in field diaries, books, unpublished reports, theses, newspapers, and other similar sources. This previously over-looked historical information is now becoming more revealing as it is added to our databases. For example, in 1947, James A. Munro and Ian McTaggart-Cowan published their treatise A Review of the Bird Fauna of British Columbia. This important book depended heavily on museum specimens and the field notes of federal biologist James A. Munro. Rarely were the observations of other active field naturalists considered or was information extracted from sources other than published literature. At the time, acceptable records, especially for rare species, were based on specimens and occasionally identifiable photographs.

· Details extracted from over 100,000 specimens of birds in museum collections around the world have been added to the ornithology dataset for British Columbia. These four specimen skins of Savannah Sparrows, collected along the coast, provide early distributional records, but more importantly they document the subspecies occurring in the province.

Over five decades later, the four-volume set The Birds of British Columbia (1990-2001) was completed. The authors attempted to include reliable observations from thousands of amateur birders as well as available unpublished government and wildlife consultant reports. Still, only a fraction of the information buried in the detailed diaries and field notebooks of early and contemporary naturalists were gleaned for records and much of the “gray” literature, including consultant’s reports, had confidentiality restrictions.

While new records help refine the known distribution of a species, we are concentrating our efforts on including more long-term biological and natural history information which indirectly also adds a “dot on a map.” For example, we have received, and entered, 61 years of arrival and departure dates for Eastern Phoebe from eight different locations within its normal range in northeastern British Columbia. The sites range from Swan Lake in the south to Fort Nelson in the north. This additional information will permit a precise calculation of change in migration dates for arrival and departure and how they vary between different years and decades.

· Many of the nearly 200 articles published in the bi-annual journal Wildlife Afield since 2004 contain new information on significant changes in the occurrence and breeding range for amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals in British Columbia. Most of these articles are available for free download by clicking on the species underlined.

Since birds are extremely mobile populations are dynamic, numbers are constantly fluctuating, and ranges are continually changing. There is now reliable evidence in our databases that over the past 120 years at least 60% of all regularly-occurring species in British Columbia have expanded their ranges. Current trend information has not considered these historical shifts in their analysis, mainly because of the time required to search and transfer old records to a central database. Two recent examples include noteworthy changes in the breeding distribution for Common Nighthawk and Canada Warbler whose numbers were considered by some to be declining.

A few other examples of species with significant changes in breeding and nonbreeding ranges in the province include Greater White-fronted Goose, Wood Duck, Gadwall, Ring-necked Duck, Harlequin Duck, Hooded Merganser, Red-throated Loon, Pacific Loon, Yellow-billed Loon, Pied-billed Grebe, Eared Grebe, Clark’s Grebe, Northern Fulmar, Brown Pelican, Turkey Vulture, Cooper’s Hawk, Merlin, Yellow Rail, Sora, Sandhill Crane, Semipalmated Plover, American Avocet, Black-necked Stilt, Greater Yellowlegs, Long-billed Curlew, Mew Gull, Heermann’s Gull at Harrison Hot Springs, Arctic Tern, Forster’s Tern, Horned Puffin, Eurasian Collared-Dove, Flammulated Owl, Western Screech-Owl, Ruby-throated Hummingbird, Vaux’s Swift, Lewis’s Woodpecker, Least Flycatcher, Dusky Flycatcher, Blue Jay, Rock Wren, Bewick’s Wren, Gray Catbird, Tennessee Warbler, American Redstart, Magnolia Warbler, Cape May Warbler, Vesper Sparrow, Black-headed Grosbeak, Brown-headed Cowbird, Common Grackle, and Yellow-headed Blackbird. Every few years a new species is discovered in the province such as Whip-poor-will in 2001, Gray Wagtail in 2004, and Pinyon Jay in 2005.

· Yellow-headed Blackbird

Provincial and state wildlife databases that include comprehensive historic and current information are the exception in North America, mainly because of the lack of commitment and interest in compiling “old stuff” that initially seems like a wasted effort with little immediate return. Yet, such information is critical in interpreting population trends, species’ annual living requirements, and reasons for changes in distribution. Long term databases are especially important in understanding how ecosystems function. Simple annual observations on the arrival and departure date for birds and emergence and hibernation dates for amphibians, reptiles, and mammals, for example, is paramount in analyzing the potential impact of climate change on vertebrates. In the long term, such information can help better focus scarce time and resources on the most important issues requiring our attention.

· Poorly known in British Columbia is the spring emergence and autumn hibernation dates for amphibians, reptiles, and mammals. Much of this information is buried in early collector and naturalist notebooks and is presently being extracted for all species, including Common Gartersnake.

Records cover a 126-year period from 1886 through 2011. It should be noted that all activities related to the data entry program are entirely volunteer-based. There are no public funds for administrative costs or remuneration for acquiring, processing, analyzing, and publishing data. The main source of dependable revenue is from our membership dues and some private donations.

The following species’ lists, including number of digital records, represent totals added to the Biodiversity Centre for Wildlife Studies species and location databases for the four-year period January 2008 through December 2011. Species underlined are cross-referenced to updated species accounts or significant extensions in breeding range published in Wildlife Afield and are available for free download.

Species below are listed alphabetically in each vertebrate group, by their common name, following the latest taxonomic standards. Species underlined are cross-referenced to articles published in Wildlife Afield. They do not include papers with lists of individual species but mainly articles that deal with only one or two species. These include diverse topics such as updated species accounts from The Birds of British Columbia (1990-2001), new provincial records, changes in distribution, noteworthy breeding records, predation, mortality, behavior, abnormalities, survey results, and unusual field observations.

AMPHIBIANS

American Bullfrog (2,624), Boreal Chorus Frog (113), Coastal Tailed Frog (11,111), Columbia Spotted Frog (837), Green Frog (21), Long-toed Salamander (93), Northern Leopard Frog (1,045), Northwestern Salamander (152), Northern Pacific Treefrog (4,517), Northern Red-legged Frog (1,499), Rocky Mountain Tailed Frog (92), Rough-skinned Newt (721), Wandering Salamander (614), Western Toad (889), and Wood Frog (1,506).

· As historical sources are gleaned for records of amphibians, new distributional information is obtained of which some is significant. For example, the first records for Northern Leopard Frog in the Okanagan Valley and Shuswap Lake region have recently been found and entered into our electronic databases.

Total amphibian species: 15 (January 2008 through December 2011).

Total amphibian records: 25,834 (January 2008 through December 2011).

REPTILES

Common Gartersnake (4,101), Gophersnake (122), Northern Alligator Lizard (1,634), North American Racer (16), Northwestern Gartersnake (109), Painted Turtle (6,418), Pygmy Short-horned Lizard (1), Red-eared Slider (2,524), Northern Rubber Boa (1,676), Terrestrial Western Gartersnake (2,536), Western Rattlesnake (189), and Western Skink (33).

· Some local populations of the three species of gartersnakes in British Columbia are melanistic. These all-black snakes are difficult to identify in the field because they usually lack characteristic markings.

Total reptile species: 12 (January 2008 through December 2011).

Total reptile records: 19,359 (January 2008 through December 2011).

BIRDS

Of the four groups of vertebrates, birds are by far the most popular and generally the easiest to identify. Hence, the ornithology database is disproportionately larger than those for amphibians, reptiles, and mammals. In the past, information was in printed form and those developing comprehensive databases could slowly poke away at the sources and enter the data into some sort of physical databank. The amount of current information today is widely scattered and is rapidly becoming overwhelming and impossible to keep on top of as new electronics are constantly being upgraded. Still, the base for any wildlife database is built upon historical information. The four-volume set The Birds of British Columbia (1990-2001), the standard reference for the province, was completed in two stages. The first two volumes, waterfowl through woodpeckers, were written from information transferred from museum specimens, field notebooks, and literature to hundreds of thousands of 3 inch x 5 inch file cards during the 1970s and 1980s. The task took over 12 years to complete! The last two volumes, the perching birds, were digitized and allowed for much quicker analysis of pertinent information.

· More than 95 percent of all records entered into the wildlife databases for the four-year period between 2008 and 2011 are of birds.

The species summary below contains two sets of numbers. The first (in italics) refers to the total number of individual occurrence records used to prepare the nonbreeding component of a species account published in The Birds of British Columbia. The second number (in bold) represents the total number of digital records currently in the BCFWS species database for the period specified. The new information, digitally entered over the past 14 years, is being used to track and update species accounts published in The Birds of British Columbia. The more comprehensive electronic database has allowed accounts to be greatly expanded. Some significant changes include the growing confidence to analyze historical changes in distribution and range, the compilation of detailed monthly distribution maps, variations in regional breeding biology, determining areas of vulnerability during a bird’s life, seasonal and regional changes in habitat requirements, and focused recommendations for conservation and management activities. Each account, which is published in the bi-annual journal Wildlife Afield, is extensive and unique in North American ornithology. Examples of updated species accounts include Canada Warbler (66 pages), Clark’s Grebe (66 pages), Common Loon (93 pages), Common Nighthawk (40 pages), Forster’s Tern (63 pages), Heermann’s Gull (53 pages), Semipalmated Plover (7 pages), Snowy Owl (83 pages), and Turkey Vulture (21 pages).

Totals for four years of data entry (2008 to 2011) are summarized below. Other years, dating back to 1997 will be added as time permits. It is estimated that the entire data set is in excess of 5,600,000 records.

Acadian Flycatcher (1 – 1), Acorn Woodpecker (1 – 8), Alder Flycatcher (498 – 2,977), Aleutian Tern (3 – 0), American Avocet (127 – 5,514), American Bittern (1,864 – 12,731), American Black Duck (522 – 924), American Coot (11,398 – 8,931),

· The current database for American Coot lacks breeding records but once entered will contain an estimated 45,000 records.

American Crow (6,336 – 11,993), American Dipper (2,717 – 17,384), American Golden-Plover (1,560 – 362), American Goldfinch (6,910 – 1,873), American Kestrel (9,608 – 3,440), American Pipit (4,357 – 5,234), American Redstart (1,911 – 3,637), American Robin (16,012 – 27,675), American Three-toed Woodpecker (771 – 528), American Tree Sparrow (1,491 – 448), American White Pelican (613 – 815), American Wigeon (17,928 – 21,169), Ancient Murrelet (1,936 – 255), Anna's Hummingbird (1,462 – 46,053), Arctic Tern (493 – 4,266), Ash-throated Flycatcher (53 – 109), Baikal Teal (1 – 1), Baird's Sandpiper (1,355 – 1,010), Baird’s Sparrow (3 – 0), Bald Eagle (19,801 – 21,141), Baltimore Oriole (234 – 133), Band-tailed Pigeon (9,373 – 1,099), Bank Swallow (1,423 – 2,997), Bar-tailed Godwit (10 – 88), Barn Owl (2,567 – 18,077), Barn Swallow (9,067 – 17,611), Barred Owl (955 – 17,091), Barrow's Goldeneye (7,101 – 24,008), Bay-breasted Warbler (31 – 3), Belted Kingfisher (8,133 – 7,491), Bewick's Wren (4,354 – 13,238), Black Oystercatcher (3,949 – 13,223), Black Phoebe (2 – 2), Black Scoter (4,063 – 4,544), Black Swift (2,144 – 245), Black Tern (1,127 – 25,120), Black Turnstone (7,690 – 2,800), Black-and-white Warbler (212 – 98), Black-backed Woodpecker (279 – 402), Black-bellied Plover (4,761 – 2,782), Black-billed Cuckoo (22 – 0), Black-billed Magpie (4,236 – 8,209), Black-capped Chickadee (9,113 – 12,964), Black-chinned Hummingbird (402 – 3,595), Black-crowned Night-Heron (262 – 714), Black-footed Albatross (974 – 1,073), Black-headed Grosbeak (1,823 – 1,973), Black-headed Gull (21 – 64), Black-legged Kittiwake (3,347 – 11), Black-necked Stilt (23 – 201), Black-throated Blue Warbler (6 – 200), Black-throated Gray Warbler (1,683 – 1,775), Black-throated Green Warbler (185 – 0), Black-throated Sparrow (19 – 2), Black-vented Shearwater (9 – 9), Blackburnian Warbler (6 – 2), Blackpoll Warbler (742 – 232), Blue Grosbeak (2 – 0), Blue Jay (355 – 1,082), Blue-gray Gnatcatcher (3 – 3), Blue-headed Vireo (201 – 49), Blue-winged Teal (5,113 – 11,344), Bobolink (572 – 85), Bohemian Waxwing (3,213 – 3,449), Bonaparte's Gull (11,758 – 950), Boreal Chickadee (1,075 – 1,679), Boreal Owl (191 – 817), Brambling (107 – 72), Brandt's Cormorant (7,259 – 9,508), Brant (7,467 – 8,632), Brewer's Blackbird (7,511 – 1,199), Brewer’s Sparrow (484 – 2), Bristle-thighed Curlew (2 – 4), Broad-winged Hawk (21 – 469), Brown Creeper (3,450 – 9,813), Brown Pelican (61 – 149), Brown Thrasher (32 – 34), Broad-tailed Hummingbird (2 – 0), Brown-headed Cowbird (5,752 – 6,526), Buff-breasted Sandpiper (113 – 70), Bufflehead (14,410 – 24,808), Buller’s Shearwater (74 – 71), Bullock's Oriole (1,740 – 1,199), Burrowing Owl (462 – 1,228),

· The large number of Burrowing Owl records is partly from new breeding locations and old observations discovered in historical field notes.

Bushtit (2,924 – 4,759), Cackling Goose (416 – 596), California Gull (4,707 – 555), California Quail (10,819 – 6,404), Calliope Hummingbird (1,568 – 1,817), Canada Goose (22,490 – 26,128